A few years ago, my husband and I got deep into the Danish political drama Borgen – the only show that has ever managed to make the topic of oil rights in Greenland sexy. In the show, Birgitte Nyborg, a fictional Danish politician, wins a surprise victory as Prime Minister and has to juggle a bunch of competing interests in order to hold on to power.

It's a great show, and it has veritas – it was based on real Danish political parties – but it feels like a fantasy viewing in the U.S., a country that has never had a female President. The two times we’ve tried putting a woman at the top of a ticket, she lost to Donald Trump, one of the most widely disliked and polarizing candidates in history. I’m not claiming that gender alone explained those defeats – both the Clinton and Harris campaigns were fraught for many reasons – but it’s tempting to speculate whether a male candidate with identical policies could have prevailed in either election. Moreover, every time the Democrats nominate a woman, men back away from the party. In 2016 and 2024, when Democrats ran female candidates at the top of the ticket, the gender gap in party affiliation was greater than in 2012 or 2020.

The dearth of female leadership is not unique to the White House: only 24% of U.S. state Governors and 28% of Congress members are women.

The depressing conclusion seems to be that if the Democrats want to win back voters (especially male voters), they should stop asking them to vote for women.

But voters in other countries are quite willing to vote for women. Among wealthy democracies, the U.S. has an unusually low representation of women in government. Across peer (OECD) nations, about 34% of parliamentary leaders are female, but this proportion is higher in Nordic countries (which average over 40% female representation). Several countries (including Mexico and New Zealand) have achieved 50-50 parity. Moreover, there is no evidence that males are systematically less likely to support female candidates than male candidates in these countries.

So is the U.S. just more sexist? Not necessarily – we actually have higher representation of women in the work force (77%) compared to the rest of the OECD (67%). So there’s a weird disconnect here: women have made economic gains, but they’re hitting a political glass ceiling.

It turns out that the issue might not (just) be sexism, but the way we vote.

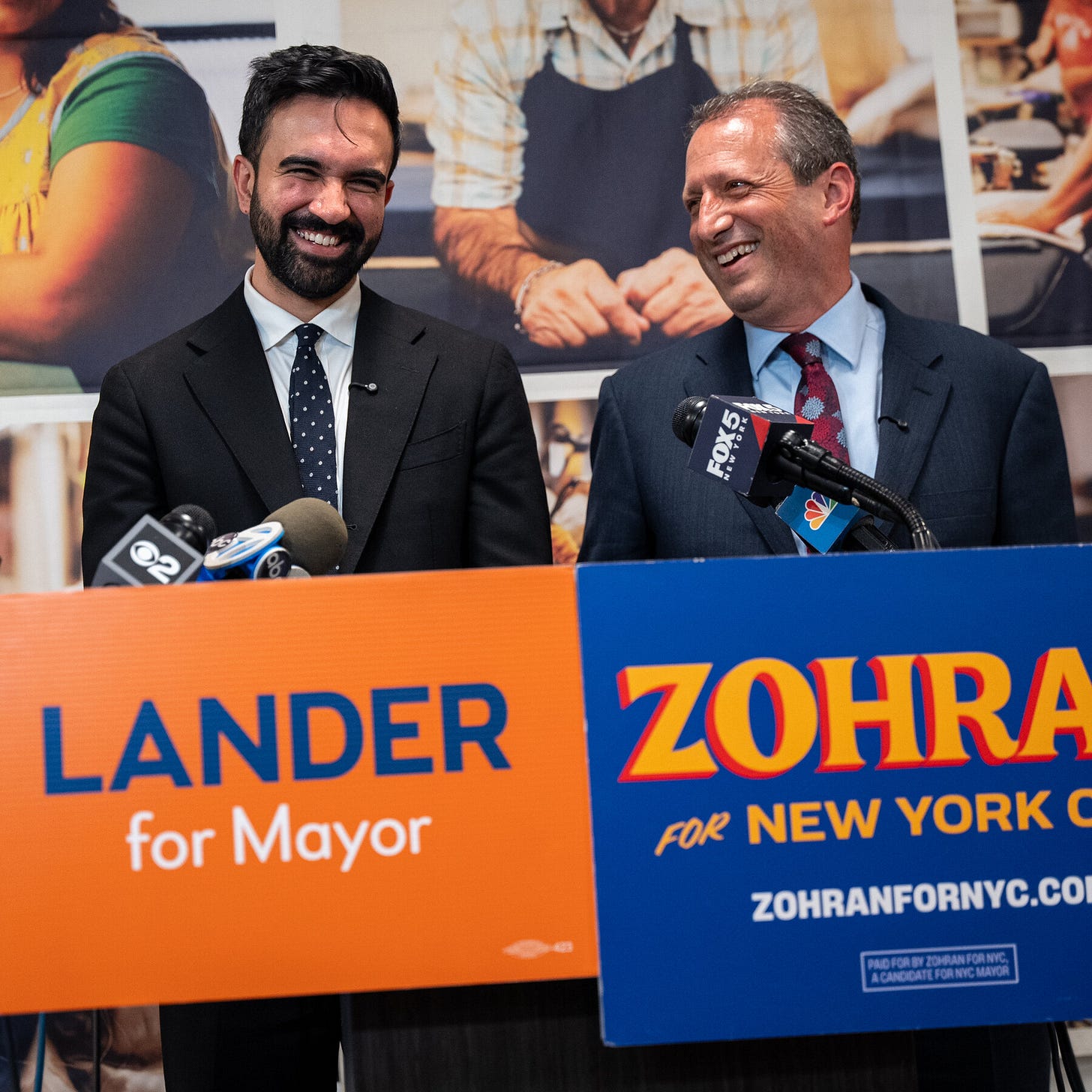

The New York City mayoral primary put ranked-choice voting into the spotlight. Zohran Mamdani used plastic cups of mango lassi to explain it in a recent campaign video. In an RCV system, voters rank their top five choices in order of preference, and you can gain vote share even if you’re not the first choice pick. That creates an incentive for candidates to build coalitions, make compromises, and cross-endorse. In the mayoral primary, candidates like Brad Lander and Zohran Mamdani made appearances and filmed ads together. This was a refreshing shift from our usual winner-takes-all majoritarian elections, which revolve around polarizing rhetoric and a binary choice.

Around the world, many countries use proportional voting or other consensus-building approaches rather than simple majoritarian rules. This can look like ranked-choice voting. It can also mean allocating a certain number of seats based on a party’s vote share. Parties put forward a slate of candidates. The voter picks a party, rather than individual candidates, and the parties then appoint candidates from their slate to fill the slots they’ve won. That’s how Birgitte Nyborg wins her fictional election in Borgen – her party, the Moderates, becomes a compromise choice between the governing Liberal Party and the Labour Party, and gains a majority of seats. To keep power, she needs to keep a coalition consisting of the Greens, Labour, and the Moderates together in order to fend off the New Right.

Research from global groups like the Inter-Parliamentary Union and International IDEA (International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance) consistently shows that more women get elected in countries that use proportional or ranked-choice voting rather than simple majoritarian systems. A picture is worth a thousand words here:

The blue bars show countries that use proportional voting systems, majoritarian systems are in red, and mixed systems are shown in grey. It’s clear that the bluer the bar, the higher the percentage of women in leadership.

In proportional systems, people pick parties, which means they focus more on policy differences. But in a winner-take-all system, a candidate’s persona become the most salient driver of voter choice. This activates deep-seated tropes about leadership. Trump is the epitome of a personality-driven candidate: he’s fueled by vengeance and personal grievance, has few real convictions, and rarely gets specific about policy. Clinton and Harris were very different candidates, but they fell into familiar, gendered traps; both women were seen as fake, transactional, and calculating. In contrast, Trump could dominate news cycles with his chaos and clownmanship. The dude literally stood up on a debate stage wearing bronzer and said that migrants were eating people’s pets, but people saw him as the safer pick— blustering and manly. When there’s a binary choice between two people, many voters feel compelled to pick the man.

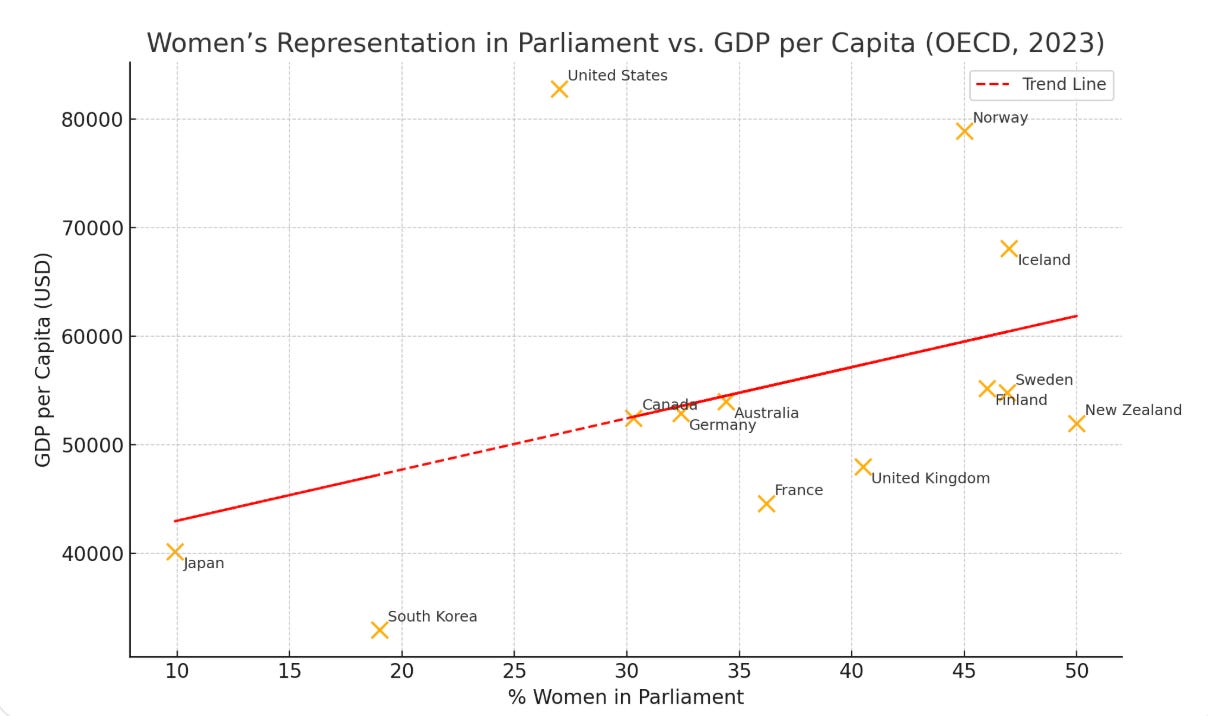

The lack of female representation in U.S. politics costs us, because there’s solid evidence that countries with a greater proportion of female leaders are, on the whole, more stable, less beset by political corruption, and more likely to invest in education, healthcare, and pro-family policies like parental leave and high-quality childcare.. Female leadership is even moderately correlated (+0.40) with national GDP:

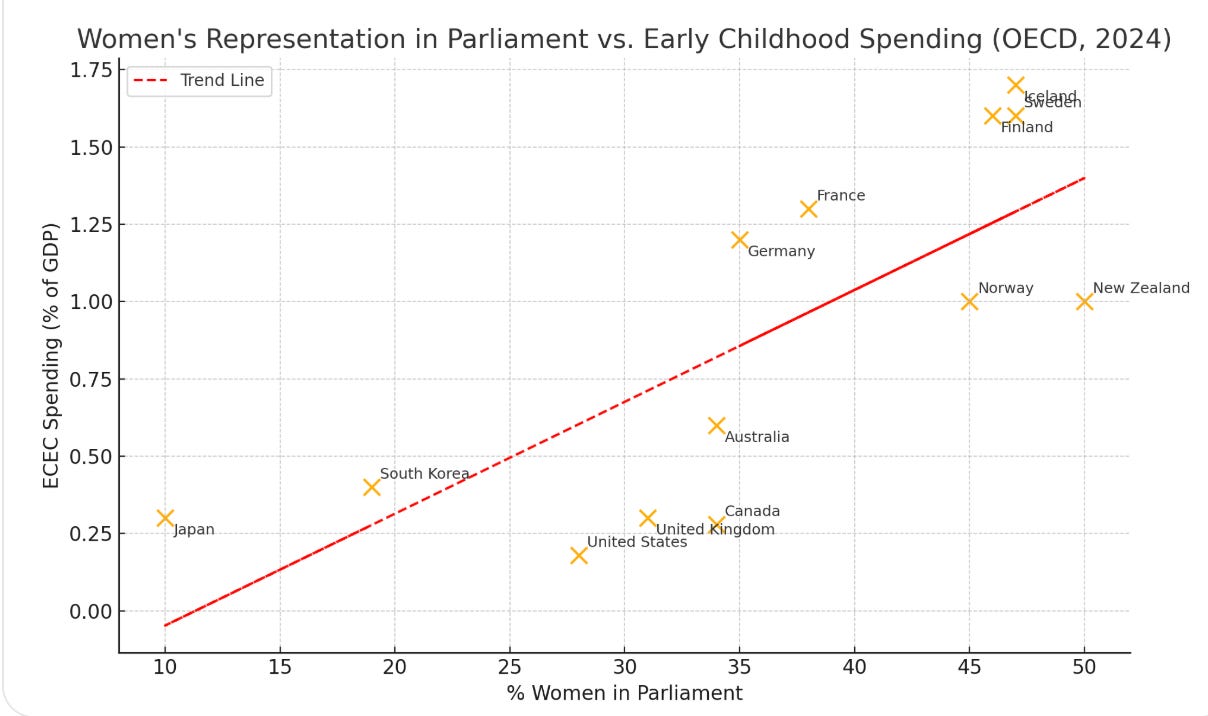

There’s also a very strong positive correlation (+0.76) between women’s representation in political leadership and spending on early childhood. Early childhood spending is a particularly cost-effective investment for countries to make - there’s evidence that every dollar spent on early childhood returns at least $4 or $5 back to the economy in terms of productivity and future growth.

Of course, there are plenty of terrible female politicians, here and abroad. Electing women is not an end in itself.

Rather, there may be a third variable explanation for the benefits of female leadership. That is, a political system that makes it easier to elect women comes with other advantages that improve national governance. Since they require more consensus-building and party alliances, proportional voting systems reward candidates who can find compromise. (You could argue that they also allow for the elevation of fringe voices, like the insurgent far-right nationalist parties now seeping into Europe. Then again, those fringe voices are currently in charge here in the U.S., so I’m not sure we’re in better shape).

Thanks to gerrymandering and partisan echo chambers, the political parties have gotten more polarized in the U.S. As a result, there is little incentive for leaders to reach across the aisle. We’ve gotten used to the idea that big agenda-setting legislative packages, like Trump’s Big Beautiful Bill and Biden’s Build Back Better, must be rammed through purely on party-line votes with zero votes or even input from the opposition.

This creates gridlock and hostility. It also erodes political stability. In the U.S., we’ve become used to wild swings in the country’s direction every time a new party seizes power and tries to dismantle everything the previous administration did. We went from redoubling green energy investments to canceling green energy deals in a head-spinning turnaround, for example. It’s hard for companies and organizations to plan. You don’t see such strong pendulum swings in countries that are governed by multi-party alliances.

Proportional voting wouldn’t solve all our problems, but it might create better conditions for compromise. It’s a fun thought experience to think about the coalitions that might form in the U.S. if we had more than two parties, and if parties needed to form alliances in order to govern. Let’s say we have a Bernie Sanders style economic populist party, a religious conservative party, an environmentalist party, a libertarian/techno-right party, and a culturally leftist party. Where could these groups find common ground? Which issues would get more attention?

Of course, it’s very unlikely that we’ll switch up our presidential voting system any time soon - it would require a constitutional amendment. But ranked-choice voting and other alternative voting approaches have gotten traction in many localities, including NYC. Maine, Alaska, and the District of Columbia have also experimented with RCV. Cities including Cambridge, MA and Minneapolis use Single Transferable Voting - a true proportional method. At the same time, seventeen states, all red states, all banned RCV between 2022-2025.

The problem with efforts to shift to a more multi-party system in the U.S. is that the enthusiasm for new voting approaches is mostly on the left. It’s easy to imagine insurgent third, fourth, and fifth parties that siphon votes from Democrats and lead to even more electoral defeat. Indeed, the third party movement gets bad PR every time a party like the Greens runs a spoiler that undermines a high-stakes presidential election and sends votes to the GOP. The action needs to happen at the local and state level. There may be an opportunity to build alternative parties in red states where the Democrat brand seems hopelessly tarnished, or in solidly blue localities where progressives will prevail either way. There are clearly multiple competing factions within the MAGA movement - some of them coming to the fore now, with the Iran conflict - and this coalition may splinter when Trump is no longer on the scene.

Trump’s presidency has undermined the strength of democratic institutions that once seemed rock-solid. This is bad, but one small silver lining is that, when you dismantle, you start to be able to imagine wholly new systems that could work better.

Sad to say I live in a state that just preemptively banned ranked-choice voting (Missouri). (We also preemptively banned plastic bag bans when those were starting to get traction, ugh.)

I really enjoyed this Freakonomics ep about understanding our political system as a duopoly much like Coke and Pepsi are a duopoly.

https://freakonomics.com/podcast/americas-hidden-duopoly_radio/

Great arguments, Darby. I really do believe that many of our political problems in this country could be solved, or at least addressed more fully, if we could get out of a two party system. A parliamentary system, where the party selects the leader, does seem to provide much better outcomes on the whole. The part about ranked choice voting or parliamentary systems privileging ideas and policies rather than features of individual candidates makes very good sense to me, as does the notion that people are more skeptical of electing women in the United States in a race like the presidency, which is so often driven by personality and who you want to have a beer (Chardonnay?) with.