Is pronatalism the same as ethnonationalism?

Why efforts to preserve a particular gene pool are quixotic, and the birth rate is a global concern

I wasn’t originally planning to write this piece: I had posts queued up this week about subsidizing part-time work for parents and universal basic income for caregivers. But then the white nationalists on Substack discovered my last post, about why immigration is good for birth rates, and yelled at me for a week. I got way too invested in the comments section, so here we go. Back to originally scheduled programming soon.

I am a pronatalist because I like babies. They are delightful! I want to live in a world where there are more babies, and especially a world where people who want to have babies get to have as many babies as they want. As a researcher who studies how the transition to parenthood affects the body and brain, I am curious about the factors that make people want to become parents, and the barriers that prevent them from doing so. Declining global birth rates worry me, not just because I am concerned about individual families, but also economic and social futures: the prospect of a world where aging retirees outnumber the young workers who care for them, where maternity wards and preschools sit empty while nursing homes fill up. Not only does that world sound lonely and kind of a bummer, but it will be unstable. Just look at all the apocalyptic novels, from Children of Man to The Handmaids Tale, that start with a birth drought.

So: I want more babies to be born, and therefore I am a pronatalist. Because I’m a patriotic American and also a selfish person, I’d like at least some of those babies to be born in the United States and to eventually join our economy so their workforce contributions can help to fund my hopefully long and luxurious old age.

I’m giving this long-winded explanation of why I consider myself a pronatalist because I’ve spent the last week on Substack being told I am not a real pronatalist. That’s because I do not care about whether the babies that I want to be born belong to a specific race or ethnicity. I do not care if they are white, brown, or any shade in between. Like I said, I like babies, and they’re all pretty cute as far as I’m concerned.

So is it true that in order to be a pronatalist you also have to be an ethnonationalist who specifically wants more babies of your ethnicity (and let’s be honest, that mostly means white babies)? That’s not what the Merriam-Webster dictionary thinks (it defines pronatalism simply as “encouraging an increased birthrate”) or what Wikipedia thinks (it calls natalism “a policy paradigm or personal value that promotes the reproduction of human life as an important objective of humanity”), and it’s not what progressives who care about the birthrate thinks, but it is certainly what many Substackers think, and it’s also what the MAGA pronatalists implicitly think. They don’t want immigrants coming to the U.S. and having babies here. This strain of pronatalist sees the need to have babies not just as a bulwark against economic decline, but as an attempt to preserve a particular culture or gene pool. If you only want certain kinds of babies, it helps explain some of the odd disconnects between Trump’s proclaimed desire for a “baby boom” and his policies that hurt actual mothers and babies, like cuts to Medicaid and Head Start and cruelty towards immigrants. If we only care about wealthy white babies, making life harder for every other baby is no problem.

But the problem with ethnonationalist pronatalism, besides the obvious problem (it’s racist!) is that it’s fueled by a poor understanding of what it actually means to talk about ethnicity, race, genetics, and culture. Efforts to preserve a particular culture by guarding its gene pool are quixotic, because both gene pools and cultures inevitably evolve over time to incorporate new and disparate influences. This is especially true in the United States: as I wrote in my last piece, if there’s anything you can say about the qualities that define our national identity, it’s that they are the qualities of immigrants, who cross oceans and mountain ranges to make a better life and find opportunity. When you talk about New York style hustle or Midwestern ingenuity or Hollywood makeovers, you’re describing immigrant values.

One of the concerns of the ethnonationalist pronatalists is that new immigrants will dilute an existing gene pool with their “low IQ” stock. I’m putting “low IQ” in quotes because the descriptor is ridiculous. As a psychologist, I was trained to administer IQ tests, and I know first-hand how culturally contingent they are. When I learned the WAIS back in the early aughts, one of the actual test questions was about putting a letter in a mailbox. Not a relevant question for, say, an indigenous person. Moreover, IQ is only partially heredity – about 50% genetic – and is also shaped by culture and environment. National IQs increase as literary rates rise, or as access to clean water and nutritious food increases. IQs get lower when people experience lead poisoning or early deprivation, like orphans in Romania or malnourished children in North Korea. In other words, IQ is at least partially a policy outcome. Any time someone posts something that confidently states an average IQ within a particular race or ethnicity, it’s a giveaway that their understanding of heredity effects on intelligence likely stopped with Hernstein & Murray’s The Bell Curve, which was published in 1994 and widely debunked at the time. Hernstein and Murray are a psychologist and political scientist, not geneticists, and their conclusions have been even more soundly challenged now that we have more contemporary DNA science that refutes the idea of “national IQs.”

Ethnonationalism is premised not just on the idea that certain ethnic groups are smarter or better than others, but that ethnic groups represent unitary or static entities rather than dynamic and evolving ones. In truth, we are all mutts, and we share much more of a global common heritage than many of us realize.

As an example, let’s look at the common claim that Mexican or Central American immigrants will not fit in with U.S. culture as well as previous waves of immigrants did, because they are just “too different” from the white Europeans who mostly made up those earlier waves. Of course, parts of the U.S. were originally in Mexico for centuries, so you could argue that places like Arizona, New Mexico, California, and Texas already have a deeply rooted Hispanic heritage; it’s important to be specific when we talk about “American culture,” because it differs from place to place. (This is another plug for Colin Woodred’s book, American Nations, which I mentioned in my last piece, and which traces how patterns of migration shaped regional identities in the U.S.). Moreover, Mexicans and Central Americans are themselves multiracial, or mestizo. But it’s also a historical whitewash, because people from different parts of Europe were seen as extremely different from each other when they first showed up in the United States. The perceived distance between a Polish person and an Irish person, or an Italian and a Brit, was incredibly vast. These groups spoke different languages, practiced different religions, had different customs and histories, and upheld different values. If you read Agatha Christie novels from as recently as the 1950s, you’ll find casual racism directed at everyone from the French to the Slavs. Ethnonationalists who want to preserve some kind of white “American” identity ignore the fact that your average American is a mishmash of these multiple separate European cultural groups which were once viewed as wildly, irreconcilably disparate.

My dad got really into geneaology when I was a kid, so I grew up with weird depth of knowledge about my ancestors. Our summer vacations often featured trips to the cemetary to look at old family gravestones, and I was the annoying kid who showed up to Family Tree day at school with a ream of names and dates. My family history is typically American: I grew up in Ohio, but before that, my people came from New York, New Jersey, Massachusetts, and Pennsylvania by way of Germany, Poland, Scotland, and England, with quite a few wild card forebears thrown in there too. My husband is Irish Catholic and French Canadian, so our kids are an even more variegated combo of identities, plus we have all adapted to our local California culture, which means we eat more tacos than sauerkraut or brisket. The one thing that almost all my ancestors had in common is that they were poor, hungry, desperate, and illiterate when they showed up on our shores, and the people here did not cheer their arrival.

OK, you might say, but your ancestors came (mostly) from Europe. But who are Europeans, really? The geneticist David Reich, whose lab sequenced ancient human genomes in 2016, found that we are a mix of indigenous hunter-gatherers, Eurasian hunter-gatherers, Neolithic farmers from the Levant/Anatolia (now modern Turkey), Neolithic farmers from Iran, and herders from the Pontic-Caspian steppe. Indo-European languages are spoken in places as far flung as India, Iran, England, and Russia. In other words, “white” people are made up of bits and pieces from not just Europe, but populations including Iran, Turkey, India, and probably Mongols, Huns, North Africans, and whoever else washed up on our shores. (The Finns are one of the few groups that share little linguistic or genetic overlap with the rest of Eurasia).

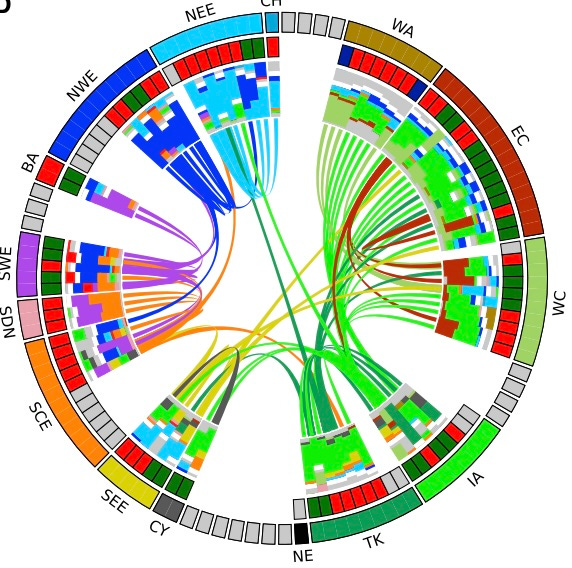

Map of Eurasian genetic admixture between 1000 BCE and 1950, published in Cell Biology; the authors state, “It is clear that migration and admixture have been the norm, rather than the exception, in human history.”

Indeed, it turns out that national identities or ethnic labels are poor proxies for genetic groupings. As the Harvard statistical geneticist Sasha Gusev writes, the newest science tells us that not only is race/ethnicity a cultural rather than a genetic construct, but:

Race is a poor causal model of human evolution. In truth, genetic variation follows a "nested subsets" model, where all people eventually share ancestors, which is fundamentally different from race. race-like models do not fit well to the genetic distances we observe even in highly geographically distinct populations with minimal admixture (and as we'll see, mixture is very common). Trying to make a racial model work produces nonsense.

Gusev goes on to make a very important point: when it comes to group distinctions on pretty much any trait, the differences within populations are almost always larger than the differences between populations. So, for example, Europeans are on average slightly taller than Asians, but the tallest Asian person is taller than the shortest European person. The height variation within those groups matters more than the averages, and knowing someone’s group affiliation doesn’t tell you much about whether they can reach the mustard on the top shelf. Although it’s true that you might find mild inherited differences between populations due to different selection pressures over time, the predictive power of these differences on an individual’s success is much weaker than, say, whether they can access health care or universal pre-K, or whether their parent is incarcerated in a foreign megaprison for daring to immigrate here with tattoos.

The most exciting recent developments in gene science are in the field of epigenetics, which has discovered that environmental stressors can actually alter DNA in ways that can persist across generations. Epigenetics research puts an additional nail in the coffin of essentialist ‘race science’ because they tell us that group distinctions are shaped by our policy choices over time.

If ethnic/racial groups are not particularly meaningful and we share more genetic commonalities than differences, the whole notion of pronatalism that boosts the births of one group over another starts to seem silly. We are all shaped by migration and assimilation, and that’s a good thing. Genetic diversity makes us hardier, more resistant to disease, better looking, and more resilient. If we care about preserving anything that unifies us, it might be cultural traditions, but cultural traditions are collective policy choices. Population-level crime and violence are policy choices, too, shaped by histories of exploitation, poverty, and inequality. Redress the poverty and inequality and people naturally behave more prosocially and societies get more cohesive. Again, that’s up to us. We can welcome new arrivals and help them find common cause with us, or we can punish and isolate them, creating worse conditions for assimilation.

The birth rate is falling globally, making pronatalism a global priority. We succeed by focusing on what unites rather than divides us: our common humanity.

If you truly believe what you believe you are going to arrive at two policy options:

1) Open Borders, we are all interchangeable worker units and africans can fund social security

2) More welfare for poor moms, since the marginal cost of an extra kid is theoretically cheaper for the poor then everyone else, and we are all interchangeable.

Though #1 might conflict with #2 since the third world is even poorer and has high fertility and so immigration could replace higher TFR in the first world and thus baby subsidies of any kind in the first world don't make sense. But I digress.

#1 is wildly unpopular across the whole world today. Basically every party left and right is moving further towards restrictionism because its been a huge failed experiment. I know you disagree but I think I'm with the median voter on this.

#2 has no support on the right. We already subsidize poor single moms to the tune of mid to high five figures a year through cash and in-kind support. I don't think there is an appetite to pour money money into that at a time when the middle class is struggling so much they aren't even having their own children.

So we will get the same proposals from the left of more means tested cash benefits for poor single moms and more money for Eds and Meds rackets full of baumol's cost disease. None of these will be popular with middle class taxpayers that have to take on that burden, and those same families will themselves have fewer children to try to afford the taxes to pay for it all.

But proposing tax breaks for large middle class families will also be unpopular with the left, who will see it as being "expensive" and mostly going to people who vote for the other party. If they do propose anything it will trend towards being in-kind (daycare rather than cash) and means tested to exclude the largest number of people they can, and fully refundable.

So basically more of what we have now.

Darby did you block the fascists? Just checking. At least that makes it easier for me find & block more of them. I didn't think that there were progressive minded pronatalists, what I've seen so far pronatalists seems to be scary patriarchal types.