Research on fatherhood and the brain is still in its infancy, and only a handful of researchers are currently focusing on dads. For me, one of the highlights of Parental Brain 2025 in Barcelona was getting to present in a symposium alongside a few of them. A few days ago, I wrote about Susana’s Carmona’s amazing keynote presentation on the maternal brain. Next, it’s our group’s turn. Our line-up includes two human researchers and two animal researchers. I’ll tell you about the human work today and save the animal work for another post.

Image credit: Maria Paternina Die

My talk is first in the line-up. I remind the audience that fathers are strange; in most species, males do not participate in childcare. Fathers help to raise offspring in only about 5-10% of mammals, including humans. Our human babies take a lot of time and energy to raise, so we practice cooperative breeding in which multiple alloparents assist in the upbringing of each child. Fathers can be part of the alloparenting web that helps our children thrive and may be one secret to our human resilience. But there is plenty of variability in fatherhood behavior across cultures and even across history, and it is likely that fathers’ involvement tracks with their neurobiological adaptations to parenthood.

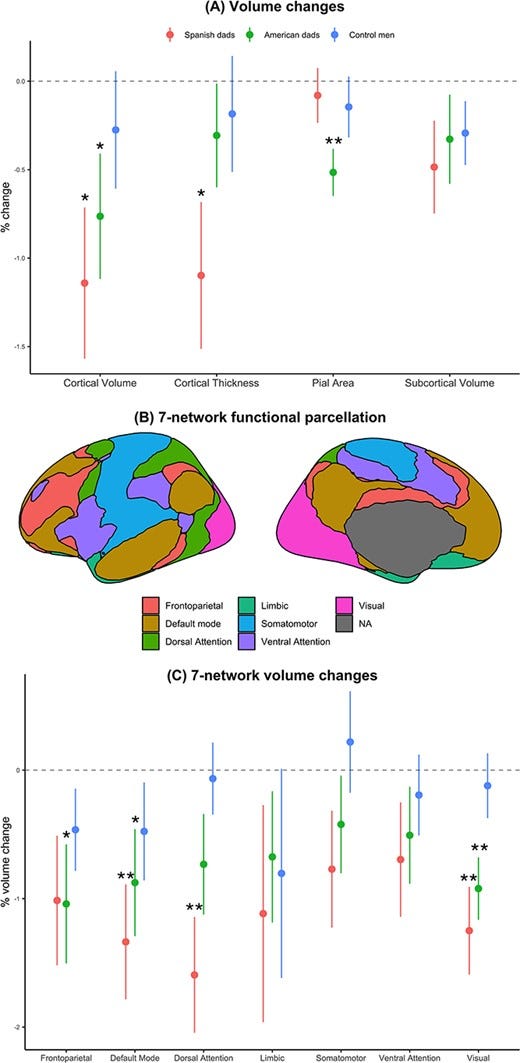

In my previous post, I told you about Susana and Elseline Hoekzema’s work finding that the maternal brain loses grey matter volume across the transition to first-time motherhood. In a follow-up study, our lab joined forces with Susana’s: we combined neuroimaging scans taken before and after birth from 20 of our California fathers, plus 20 Spanish fathers. Across both samples, we found grey matter volume reductions that echoed those found in the mothers, especially in the mentalizing network and the visual perception network. But the dads’ brains changed in ways that were more subtle, less striking, and more variable than the big-time changes seen in the mothers. That suggests that men’s individual levels of fathering engagement might matter more than an overall, universal “dad brain” effect.

When we reanalyzed our California sample of fathers with this in mind, we found indeed that dads who were motivated and more engaged in fatherhood showed larger brain volume decreases. But on the flip side, fathers who lost more grey matter volume also had worse sleep, more depression, and greater anxiety than fathers who had more minor brain changes. This might illustrate a cost of caregiving: the same brain adaptations that support parenting might also set us up for greater mental health risk. This doesn’t mean we should stop parenting, but rather that new parents may need enhanced support. Times of change are also often times of risk and vulnerability.

Next in the line-up in James Rilling, a professor at Emory who wrote the terrific book Father Nature. He describes a study that included 50 expectant fathers and 50 non-fathers, all cohabiting with their partners, scanned before and after birth. He gave the men an effort-based decision-making task in the scanner: dads could look at either a picture of a baby or a picture of an attractive female, and they had to work to get access to either type of trial by squeezing a handgrip dynamometer, a device that measures the intensity of your squeeze. Across the board, non-fathers exerted more effort (that is, they were more willing to squeeze the dynamometer) to view trials that featured the female pictures.

Before birth, there were no significant differences between the expectant fathers in their brain responses to the babies and the ladies. But at the second scan, four months after birth, the new dads had a stronger response to infant faces in the pleasure/reward regions of the brain. There was, in fact, a three-way interaction of fatherhood status, female stimuli, and infant stimuli in what Rilling calls the “fMRI pleasure signature,” such that fathers showed less of a pleasure response to females and a greater pleasure response to infants. In other words, when you become a dad, infants get more rewarding, and you’re less motivated by new mating opportunities. This research tells us that a shift in men’s reproductive priorities is underway in new parenthood, and we can see it happening in the brain.

Babies vs. ladies: An easy choice for non-dads

Rilling also looked at brain structure changes from pregnancy to four months postpartum. His results differ from our lab’s, in that he found increases in volume rather than decreases. Specifically, fathers’ brains got bigger across the transition to parenthood in regions including the insula, supermarginal gyrus, pars opercularis, postcentral gyrus, and medial orbitofrontal cortex. Collectively, these regions link sensory experiences with emotional and cognitive responses, allowing for complex behaviors like empathy, communication, and social decision-making. Moreover, fathers whose supermarginal gyrus, insula, and postcentral gyrus increased in size found parenting less frustrating.

It’s disappointing that our findings don’t match up, but a good reminder that our field is still in its early days, and that we need more, better, and bigger studies to reconcile some of the conflicting results. Given that the latest data is pointing to curvilinear brain change in new parenthood - that is, volume decreases followed by increases - we might just be catching men in different places along the change trajectory.

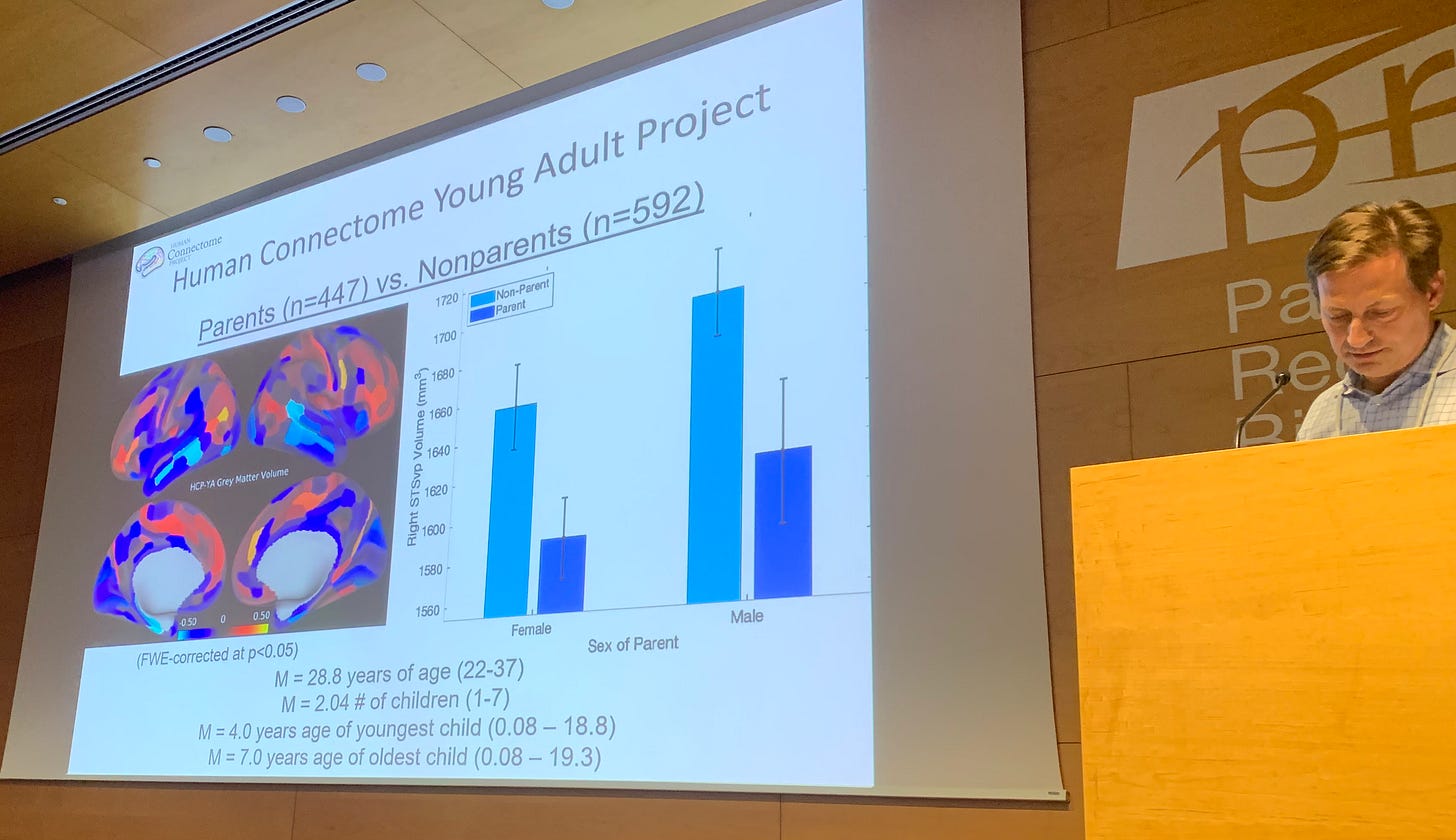

In an illustration of this, Rilling’s team also analyzed data from a bigger sample of scans, this one from a publicly available dataset called the Human Connectome (HCP) Young Adult Project. They compared brain images from 447 parents and 592 non-parents. The participants were 29 years of age on average, and the parents had an average of 2 children with ages between 4-7. This analysis yielded results more similar to the shrunken-brain findings we got in our Spanish and California dads. Rilling found that for both mothers and fathers, parenthood status was linked with less volume in right superior temporal sulcus (rSTS), a key mentalizing network region. The HCP study only had cross-sectional data; they didn’t follow people from before to after parenthood. But it is still noticeable that a difference emerged between the parents and non-parents that lines up with our other findings.

Rilling sharing the Human Connectome Project data. You can see that both moms and dads have smaller rSTS volume than non-parents

Next up in our symposium is Pascal Vrticka, a Swiss neuroscientist who is based at the University of Essex in the UK. He’s done a bunch of brain studies that include dads, and he summarizes results from a few of them in his talk. First, his “caregiver or playmate” study gave both mothers and fathers of school-aged children a ball-tossing game to play in the scanner. This game, called Cyberball, has been used in a few neuroimaging studies to see how the brain responds to social exclusion. The game starts out with a cartoon ball being tossed back and forth between the participant and a couple of kids; one child is the participant’s own, and one is an unfamiliar kid. The game is rigged so that at times, it turns into a game of keep-away, with the children tossing the ball back and forth to each other and not to the participant. By tweaking the game play at several points during the scanning session, we can see how the parents’ brains respond to being both included and being excluded from the game.

The Cyberball game that Vrticka gave parents

The big take-away from this study is that fathers and mothers had overall similar responses to the game, suggesting that there aren’t big sex differences in terms of how parents react to playing with their child. There were some subtle differences, however. In reward related, attention, theory of mind and social cognition networks, mothers showed more brain activation for inclusion vs exclusion. In contrast, dads showed more “mentalizing brain” activation to exclusion. Vrticka’s takeaway is that mothers might focus more on interacting with their children; fathers focus more on their child’s relation with the outside world, in this case with the outsider playmate.

Vrticka also gave families puzzle-solving task in which kids could either solve a puzzle with their father or mother. During the task, fathers and mothers showed similar levels of neural synchrony with their kids. Mother-child dyads had higher brain synchrony when there was more turn-taking, greater task success, and higher child agency (mothers letting their child lead the interaction).

The same findings did not emerge in fathers. However, there was a positive correlation between fathers’ beliefs about paternal caregiving and their brain synchrony with their kids. Interestingly, fathers were somewhat more strongly linked with their kids neurally, but mothers were strongly linked behaviorally. Vrticka suggests that the father-child brain synchrony might represent a “compensatory mechanism” to make up for the lower levels of behavioral alignment.

Vrticka has few ongoing studies in progress that include brain data from family triads (mother-father-kid), so there will be some cool new findings to report on soon. Overall, the lesson from this symposium is that men do show neuroplasticity when they become fathers, and that mothers and fathers are frequently more similar than different in terms of how their brains respond to child stimuli. Instead of assuming that only women are hard-wired to parent, the science is telling us that all parents are equipped with a flexible, responsive brain that tracks with participation in care. Great fathers are made, not born.