Early on the morning of Wednesday, January 8, my 15 year old daughter burst into our bedroom with her phone bleating out an emergency alert. Time to get ready, it said – you might need to evacuate soon. The Altadena fire was blazing five miles away, and an epic windstorm was pushing the smoke towards us. My husband and I were blearily waking up from a restless night of sleep interrupted by whistling winds and loud bangs. The metal casing for our old hot water heater had blown off and had been slamming rhythmically against the side of our house all night, as if we’d been sleeping inside a drum set. When we looked out the window, the sky was yellow.

We decided to head out of town while the roads were still clear. My husband grabbed guitars and we threw clothes and toothbrushes into a suitcase. Loading up our car in the smoky air, ash raining down on our shoulders, I remembered another morning 24 years ago, walking through downtown Manhattan on September 11th and recognizing that the world had just changed.

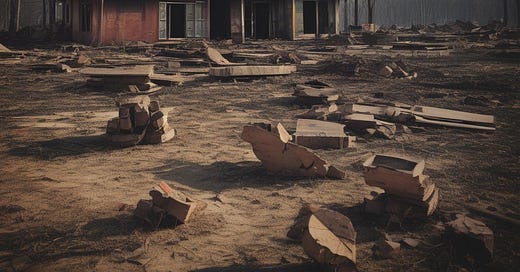

For the next few days, we hunkered down at a hotel an hour south of us, glued to TV news as we watched places we knew go up in smoke. The summer camp that my kids attended for years, friends’ backyards where we’d gathered for barbecues, hiking trails, the living room where a friend hosted her annual Christmas cookie swap party. Neighbors posted pictures of burned book pages that had scattered in their yards. By the time we got back to our house, with a blanket of ash covering our yard, we’d heard from close to a dozen friends whose homes were gone. My beloved graduate mentor lost the Pacific Palisades home where my husband and I housesat twenty years before. Former neighbors lost the Altadena dream house they had just purchased the previous year. Musicians lost their studios, costumers lost their wardrobes, house cleaners and landscapers lost their jobs, kids lost their schools, and parents lost their childcare.

And now we are confronting a rebuilding challenge of an epic scale. In the over 20 years that I have lived in LA, I have learned one universally accepted truth: real estate is impossible here. Home prices are astonishingly high. Inventory is perpetually low. And to build or renovate is to wade through a jungle of arcane codes and rules, a long wait to get plans approved by the city that might get kicked back due a minor detail that requires the whole lengthy process to start up again. As a result of these long lags, many home additions and back houses in L.A. are built on the sly, without permits. But in the long run, that compounds fire danger, because unpermitted additions often do not follow fire-mitigating safety codes.

Not only is home ownership tricky, but real estate here is full of bad actors. (And I don’t just mean people who are bad at acting, although, in L.A., that is true too). House flippers with deep pockets who buy foreclosed homes with all-cash offers, slap on some cosmetic upgrades, and sell them at jacked-up prices. Speculators who buy houses they don’t plan to live in, despite our city’s perpetual housing shortages. Investors who turn family homes into short-term Airbnbs. The incentives for speculators and flippers are to drive prices as high as they can, and there are few guardrails. There’s a builder in our neighborhood that has turned dozens of once-charming old homes into supersized white concrete boxes with black fences in front of them, all sold at exorbitant prices while our homelessness crisis grows.

I live on a modest block in Eagle Rock, a neighborhood just a quick freeway ride away from the epicenter of the Eaton Canyon fires. When we moved in 12 years ago, our block had half a dozen families with young kids who would scooter to our local elementary school together. The most two recent home sales on our block were fixer-up flips sold by investors, and their Redfin sales histories are novels in themselves. The house directly across from us was purchased in the 1970s for $25,000, and was still occupied by the same family – a couple who had raised their now-adult kids there – when we moved in. An investor bought it for a million dollars in February 2022, fancied it up, and then sold it for almost twice as much money that same October. It was purchased as an investment property and second residence by a rock star who used the house mainly to house his instruments and (according to the neighborhood rumor mill) carry out an extramarital affair, and was back up for sale less than two years later. Another house down the street from us was also originally purchased in the 1970s for $57,000, and then sold to developers in 2020 for a relatively modest $650,000. It was completely rebuilt from the ground up and then sold for over $3M to a guy who works in tech who promptly rented it out for film shoots (you might recognize it as Adam Brody’s house in Netflix’s Nobody Wants This) and used the proceeds to buy himself a Tesla Cybertruck that he parks on the street. Although it was fun to watch both houses get glow-ups, it’s ironic that the two largest and nicest houses on our block were both sold to single dudes who aren’t even there full time. Without flippers doubling and tripling the home prices, the houses might have been within purchasing reach of a family with kids who could use the space.

And this is why I’m so worried about what might happen in Altadena and the Pacific Palisades as rebuilding begins. Investors can swoop in to buy distressed, fire-damaged homes, and treat the lots as empty canvases for mega-mansions to be sold to high bidders. Without careful leadership, we could be looking at a Los Angeles where our long-standing wealth inequality gets worse and our housing shortages become even more profound. Just as the family homes on my block became side hustles for single men, so too could these deeply rooted neighborhoods sacrifice their souls – and their populations – to the churn of speculation. Altadena is a diverse neighborhood where Black families created generational wealth in their homes. Many of the Palisades blocks that were destroyed were occupied by retirees, like my graduate advisor, who bought decades before.

Yet there is also opportunity here. Never has Los Angeles encountered rebuilding needs of such epic scale, not just thousands of homes but entire blocks and commercial districts. In recent years, progressives from many quarters have advocated an ‘abundance agenda’ centered on building and growth. Abundance agenda-ites argue that Democrats need to stop being the party of red tape, over-regulation, and NIMBY roadblocks. Blue states and cities should be able to build quickly, like we did in the 1930s and 1940s.

We can now test these ideas in real time.

Newsom has pledged to streamline building codes in California to spur a faster rebuild. He released an executive order that suspends California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA) and the California Coastal Act restrictions on building, and promises to review all building code regulations to speed up permits. This is a good idea, and not just for the fire-affected areas; writ larger, it could make a dent on our city-wide housing shortages. But in the same breath, Newsom’s order specifies that these provisions only be lifted when rebuilds do not exceed 110% of the footprint and height of pre-existing properties, thereby limiting efforts to rebuild more densely.

But density is needed to fix our housing affordability crisis. Of course, individual homeowners should rebuild as they choose, typically replacing single-family homes. But many will choose to sell rather than rebuild, opening up land whose use can be re-imagined.

The fire destroyed commercial as well as residential blocks. This creates an opportunity for commercial districts to rebuild with mixed-use development – that is, an integration of commercial and residential properties that allows for more vibrant and walkable neighborhoods. Think apartments above stores, or townhouses and condos mixed in with shops and restaurants. Outdated zoning codes have kept businesses and homes far apart in much of Los Angeles, propelling the car culture the city is known for. But moving more residences into commercial blocks is not just a boon for community cohesion, it is also more fire-smart to cluster residents away from the hillsides and canyons that pose the greatest risks, and into centralized blocks with clear escape routes.

Some plots are in areas that shouldn’t be redeveloped because the fire danger is too acute. A rebuilding plan increase buffer space by leaving a greenbelt of publicly owned plots undeveloped. Greenbelts as fire buffers can also provide public park space. But in order to make that work, we need more housing density elsewhere. In 2020, Newsom vetoed a bill that would have forced local governments to enforce more stringent building codes and road design in high-fire-risk areas. Additional bills in 2022 and 2023 that restricted development in fire-prone areas but loosened density rules lower-risk areas didn’t even make it to a vote, given opposition from builders in the state. If we take density off the table now, at a time our housing shortages have never been more salient, we sacrifice a once-in-a-generation opportunity.

Newsom’s order mentions exploring the use of pre-approved plans in order to speed up permitting. This is an excellent idea that also creates opportunity for more sustainable designs. Perhaps the county sponsors a contest among architects to come up with design plans that are fire-resilient. Or forms a task force of architects with an understanding of the history and character of their neighborhoods and invites them to contribute to a repository of permitted designs. Homeowners seeking to rebuild can then choose from pre-vetted floor plans for instant approval. Of course, homeowners can hire their own architects and rebuild any way they like– but they will save time and money if they opt for designs that have been rubber-stamped.

California’s mild climate makes it a perfect place to explore innovations like “passive use” building, a movement that has gained traction in Europe. “Passive homes” are designed like airtight thermoses to minimize energy needs. These designs are also more fire resistant, because they are better insulated. City leaders could provide grants to homeowners who choose passive home or other designs that mitigate fire hazards. Passive use homes cost more upfront to build – but research from the National Institute of Building Sciences shows that every $1 spent on implementing wildfire-safe building codes can save $4 in future losses. Public investment can better harden our communities to future risk.

But who will buy the distressed homes and plots of land that will enter the market? As the fires raged in the Palisades, local news reported that real estate investors had already commissioned helicopters to survey plots that might soon become available. Coincidentally, at around the same time, New York Governor Kathy Hochul announced proposals in her state to restrict private-equity speculation on single-family homes. These include a 75-day “cooling-off period” that prohibits institutional investors from snapping up properties. It might be hard to implement a similar wait time in Los Angeles given the urgency of rebuilding, but Governor Newsom has already articulated the need for guardrails to prevent speculation. As an alternative to big-money investors, California could support community stakeholders to form a Community Land Trust, a collectively owned non-profit that holds onto land on behalf of its residents. Community members own their homes, but the CLT owns the land, which limits speculation and keeps housing affordable long-term. A CLT in Altadena or the Palisades could buy fire-damaged plots from homeowners, and then help fund the rebuilding of homes on those plots. Land stays in the community.

A smart architect told me, “What is done fast will not be good, but what is done well might be too slow.” We need to do fast and good at the same time. And we need to balance conflicting agendas: curbing speculation even as we deregulate; expediting permitting without sacrificing safety. Reconciling these priorities will require unusually careful and clear-eyed leadership, but this is a city of big dreams. Los Angeles is an impossible city, held together with glitter and gaffer’s tape, but nobody does a better makeover.